DIRK VERMEERSCH STORY

WHEN BEER IS ON THE FINISH LINE

It is often said about racing car drivers that they have several lives. Belgium’s Dirk Vermeersch, a former driver himself, is living proof that they do. An erstwhile taxi driver, he soon shifted gears, opting for a career on the racing track. Due to a serious accident, however, his career came to a screeching halt, and he was forced to live at nature’s pace, under the French sun, surrounded by vineyards. Recently, he has switched his allegiance from Bacchus to the nectar of barley, launching into a new career as a brewer.

Some people are born to triumph. But despite this, nothing can be taken for granted, and to accomplish their goals, a well-planned scheme is required. Plan Vermeersch undeniably bears the stamp of success.

1977 Barely two years after starting his career as a racing driver, Dirk had already climbed to the highest step of the podium, winning the first 24 Hours of Zolder. His life in the fast lane, however, would come to a grinding halt after a rally accident in 1986. Dirk was forced to leave the racing track and take up a more sedentary life as a car dealer, selling mostly top Italian makes such as Lancia and Maserati.

With the new millennium comes a change of direction

2000 Dirk permanently left the car industry and his homeland for Tulette, the South of France, starting up a B&B in the Rhone Valley and taking some down time. But when you’ve spent your life with your foot on the gas, it is difficult to settle for the dolce vita in the sun. So where better place to produce wine! Dirk Vermeersch bought half a hectare of Carignan vines around forty years old. True to Plan Vermeersch, less than two years later, one of his wines – GT-Syrah – would garner an accolade. Since 2005, his daughter Ann and son-in-law Sébastien have entered the scene and in 2010 a brand-new winery broke ground in Suze-la-Rousse.

Returning to his roots

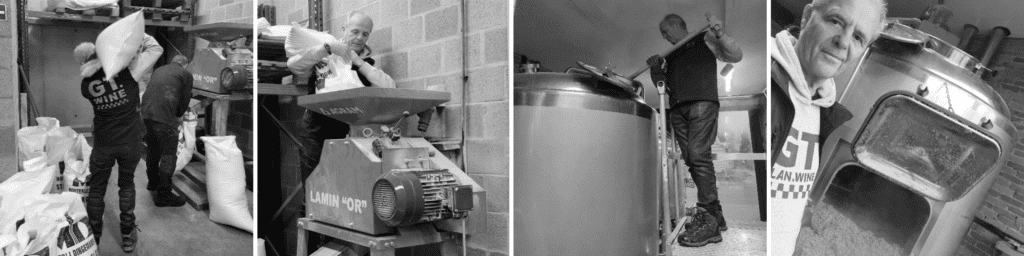

2020 With the new generation at the helm, Dirk knew that his wine business was in good hands and that it was time to contemplate another plan. Retirement maybe? Dirk returned to Belgium and soon started to get bored. So, what is there to do in Belgium? Make beer of course!

The beer industry was not entirely uncharted territory for someone who had the colours of Carling Beer on his first ever podium at 24 hours Spa-Francorchamps and had the logo of Westmalle Trappist on his Racesuit in Daytona. His circle of friends also includes former Witkap brewer (Brasschaat), Gunther Luyten. But to become a brewer oneself is a whole new ball game. After six months of self-teaching, an online brewing course – due to Covid – and some experiments, he was ready to release his LePlan Triple.

As we gear up for summer, LePlan Extra and LePlan IPA offer a breath of fresh air, and another side of Plan Vermeersch revs into action. And if history repeats itself, there is every likelihood that within the next two years, his new beers will also garner accolades on Belgium’s craft scene. Dirk Vermeersch is sitting on a (liquid) gold mine.

BELGIAN CRAFT BEER

BELGIAN BEER IS PROBABLY THE BEST IN THE WORLD

A new wind is blowing through the rich Belgian beer landscape, loosely inspired by the American and international craft beer revolution. The latest batch of Belgian brewers are reconciling tradition with experimentation in a varied, seemingly inexhaustible, stream of new beers.

In Belgium, beer was already produced in the Roman era, as evidenced by the excavation of a brewery and malthouse from the 3rd and 4th centuries AD at Ronchinne. During the Early and High Middle Ages, beer was produced with gruit, a mix of herbs and spices that was first mentioned in 974 when the bishop of Liège was granted the right to sell it at Fosses-la-Ville.

From the 14th century onwards, gruit was replaced by hops, after the example of imported beers from northern Germany. After that, several Belgian towns developed their own types of beer for export to other regions, most notably the white beer of Leuven and Hoegaarden, the caves of Lier and the uitzet of Ghent.

Monasteries played only a small role in beer production and mostly brewed for their own consumption and that of their guests. Monastic brewing would only receive some renown from the late 19th century onwards, when the trappists of Chimay produced a brown beer that was commercially available.

In 1885, a change in legislation made brewing of German-style bottom-fermenting beers viable in Belgium, and it was only from then that large industrial-scale brewing in Belgium took off.

During the 20th century the number of breweries in Belgium declined from 3223 breweries in 1900 to only 106 breweries in 1993. Yet, a number of traditional beer styles, such as white beer, lambic and Flemish old brown were preserved, while new local, top-fermented styles developed, such as spéciale belge, abbey beer and Belgian strong ale or Triple.

In 2018, there were approximately 304 active breweries in Belgium, including international companies, such as AB InBev, traditional breweries including Trappist monasteries and hundreds of small local familly breweries.

In 2016, UNESCO inscribed Belgian beer culture on their list of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

Belgium exports almost 80% mostly across Europe, US and China. Cafés, exclusively or primarily offering Belgian beers, exist beyond Belgium in France, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States, amongst others.

Some beer festivals outside Belgium have a Belgian beer bar as an alternative to local products. In North America, a growing number of draught Belgian beer brands have started to become available, often at “Belgian Bars”.